This article explains why dark matter is called 'dark', emphasizing that it's not because it's a shadowy substance, but rather because it doesn't interact with light. Unlike regular matter, which can absorb and scatter light, dark matter lacks an electric charge and therefore cannot connect with light.

The reason we call dark matter dark isn’t because it’s some shadowy material. It’s because dark matter doesn’t interact with light. The difference is subtle, but important. Regular matter can be dark because it absorbs light. It’s why, for example, we can see the. This is possible because light and matter have a way to connect. Light is an electromagnetic wave, and atoms contain electrically charged electrons and protons, so matter can emit, absorb and scatter light.

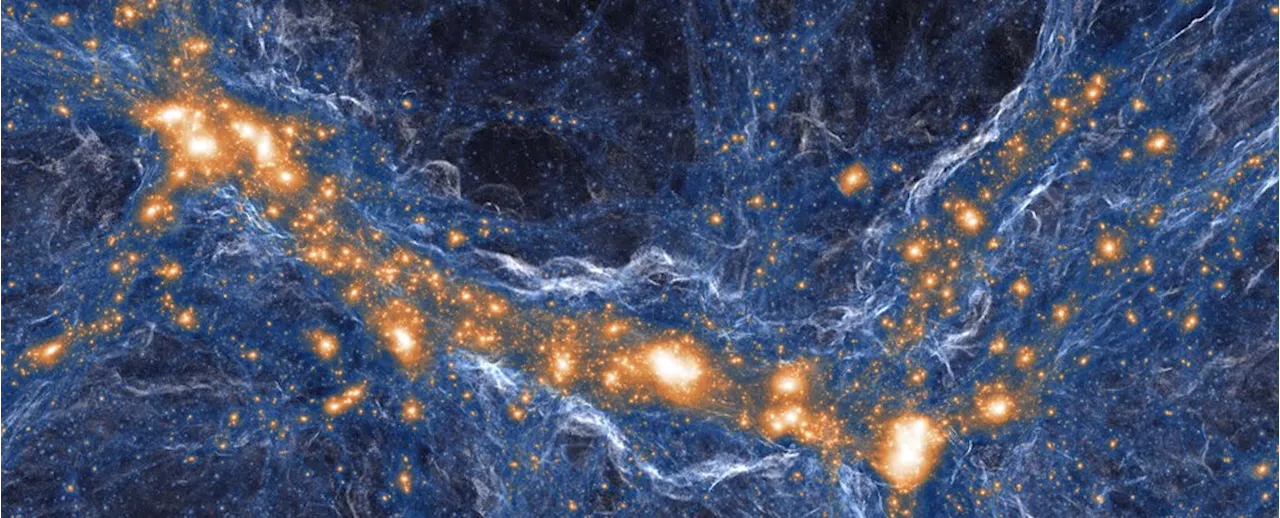

All of our observations suggest that dark matter and light only have gravity in common. When dark matter is clustered around a galaxy, for example, its gravitational tug can deflect light. Because of this we can map the distribution of dark matter in the Universe by observing how light is gravitationally lensed around it. We also know that dark and regular matter interact gravitationally. The tug of dark matter causes galaxies to gather together into superclusters.

Since we haven’t directly observed dark matter particles we can only speculate, but most dark matter models argue that gravity is the only common link with light and regular matter. Dark and regular matter clump around each other, but they don’t collide and merge like interstellar clouds. But a new study suggests the twoThe study looks at six ultrafaint dwarf galaxies, or UFDs. They are satellite galaxies near the Milky Way that seem to have far fewer stars than their mass would suggest.

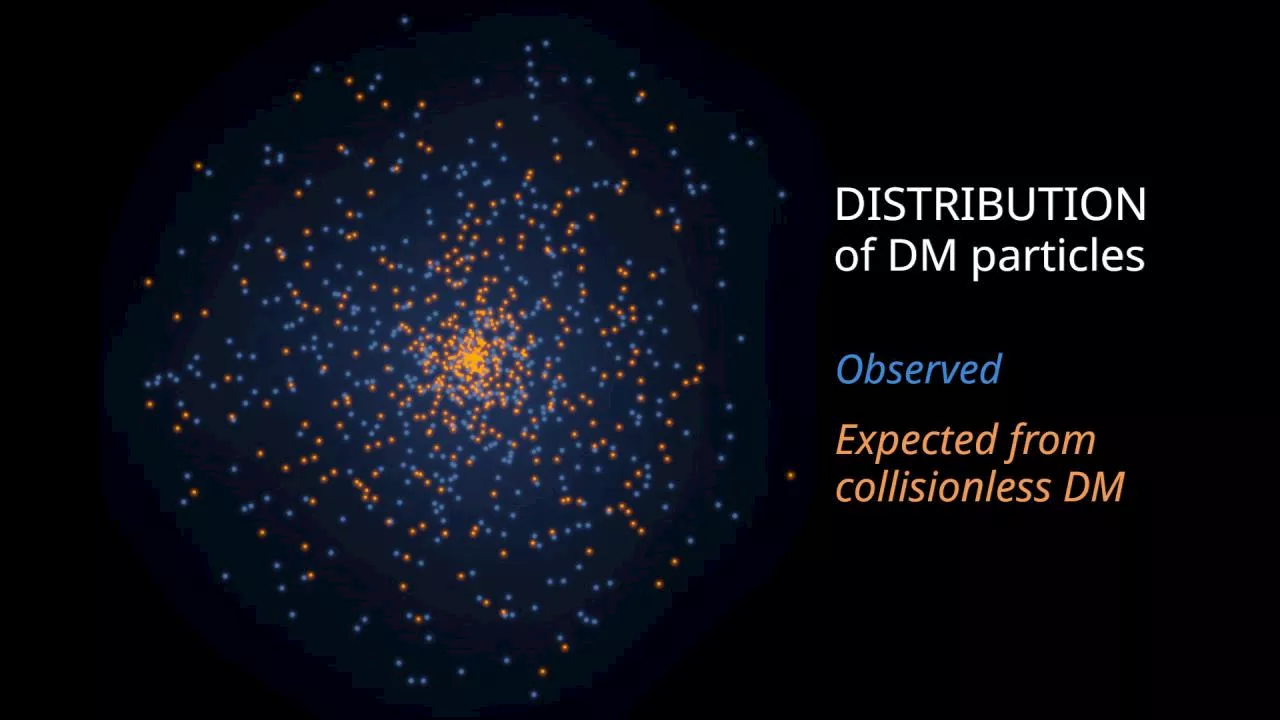

To test this the team ran computer simulations of both scenarios. They found that in the non-interacting model the distribution of stars should become more dense in the center of the UFDs and more diffuse at the edges. In the interacting model the stellar distribution should be more uniform. When they compared these models with observations of the six galaxies, they found the interacting model was a slightly better fit.

So it seems dark and regular matter interact in ways beyond their gravitational tugs. There isn’t enough data to pin down the exact nature of the interaction, but the fact there is any interaction at all is a surprise. It means that our traditional models of dark matter are at least partly wrong. It may also point the way toward new methods of detecting dark matter directly. In time we may finally solve the mystery of this dark, but not entirely invisible, material.

Dark Matter Light Gravity Electromagnetic Waves Astronomy

United States Latest News, United States Headlines

Similar News:You can also read news stories similar to this one that we have collected from other news sources.

Largest Dark Matter Detector is Narrowing Down Dark Matter CandidateSpace and astronomy news

Largest Dark Matter Detector is Narrowing Down Dark Matter CandidateSpace and astronomy news

Read more »

Dark Matter May Interact With Regular Matter Beyond Gravity, Study FindsThe Best in Science News and Amazing Breakthroughs

Dark Matter May Interact With Regular Matter Beyond Gravity, Study FindsThe Best in Science News and Amazing Breakthroughs

Read more »

Dark matter could have slight interaction with regular matter, study suggestsThe reason we call dark matter dark isn't that it's some shadowy material. It's because dark matter doesn't interact with light. The difference is subtle, but important. Regular matter can be dark because it absorbs light. It's why, for example, we can see the shadow of molecular clouds against the scattered stars of the Milky Way.

Dark matter could have slight interaction with regular matter, study suggestsThe reason we call dark matter dark isn't that it's some shadowy material. It's because dark matter doesn't interact with light. The difference is subtle, but important. Regular matter can be dark because it absorbs light. It's why, for example, we can see the shadow of molecular clouds against the scattered stars of the Milky Way.

Read more »

Shawn Mendes' Smoldering Twitter ComebackWhy, why, why would you post that picture, Shawn?

Shawn Mendes' Smoldering Twitter ComebackWhy, why, why would you post that picture, Shawn?

Read more »

Laughter and Humor 101Why we laugh, why we don’t, and why it matters

Laughter and Humor 101Why we laugh, why we don’t, and why it matters

Read more »

Did dark matter help black holes grow to monster sizes in the infant cosmos?Robert Lea is a science journalist in the U.K. whose articles have been published in Physics World, New Scientist, Astronomy Magazine, All About Space, Newsweek and ZME Science. He also writes about science communication for Elsevier and the European Journal of Physics. Rob holds a bachelor of science degree in physics and astronomy from the U.K.

Did dark matter help black holes grow to monster sizes in the infant cosmos?Robert Lea is a science journalist in the U.K. whose articles have been published in Physics World, New Scientist, Astronomy Magazine, All About Space, Newsweek and ZME Science. He also writes about science communication for Elsevier and the European Journal of Physics. Rob holds a bachelor of science degree in physics and astronomy from the U.K.

Read more »