How Keiko, the killer whale who starred in “Free Willy,” became free himself, after 20 years of captivity. NewYorkerArchive

It was a hell of a time to be in Iceland, although by most accounts it is always a hell of a time to be in Iceland, where the wind never huffs or puffs but simply blows your house down. This was early in August, and it was stormy, as usual, but the summer sun did shine a little, and the geysers burped blue steam and scalding water, and the glaciers groaned as they shoved tons of silt a few centimetres closer to the sea.

In 1964, the Vancouver Aquarium commissioned a sculptor to kill an orca to use as a model for an artificial one. An orca was harpooned, but it managed to survive, so the aquarium decided to make the best of the sculptor’s ineptitude and display the live whale rather than build the plastic one. The whale was named Moby Doll. She was the first orca in captivity. She died after eighty-seven days, but had been observed enough to demonstrate the species’s considerable intelligence.

Once Warner Bros. agreed to underwrite the project, Tugend and Shuler Donner went out to audition the killer whales of the world to play Willy. Twenty-one of the twenty-three orcas in the United States belong to Sea World. The company’s executives reviewed the script, shuddered at the message of whale emancipation, and declared all of its orcas unavailable for movie work. Shuler Donner and Tugend looked further.

Keiko, who had become infected with his own virus—a papillomavirus that had caused the pimply irritation on his skin—was still languishing in Mexico, but now he was in demand. The owners of Reino Aventura didn’t want to part with him, but they recognized that he was in poor health, and possibly even dying. They had already tried to find Keiko another home, having previously offered to sell him to Sea World, but Sea World hadn’t wanted a warty whale. Now, suddenly, everybody wanted him.

“It was like New Year’s Eve when he arrived,” Ken Lytwyn, the senior mammalogist at the aquarium, said recently, sounding wistful. “I’ve worked with dolphins and sea lions and even other killer whales, but Keiko was . . . different. There was really something there.” Skepticism was not the only impediment to moving Keiko to his ancestral home. Consider this: Icelandic fishermen view whales as annoying and gluttonous—blubbery fish-grinders that consume commercial product by the ton. The government has asked the International Whaling Commission to allow regulated whaling again, and Iceland recently accepted the first shipment of Norwegian whale meat in fourteen years.

The whale was not unwelcome here when he arrived, in September of 1998, even though you couldn’t see him unless you drove up to the ledge across the harbor and looked through a telescope that the foundation had installed; and even though not many local people got jobs; and even though the Keiko merchandise—the shot glasses and aprons and tea cozies decorated with his distinctive black-and-white face—wasn’t flying off the shelves in the souvenir shops.

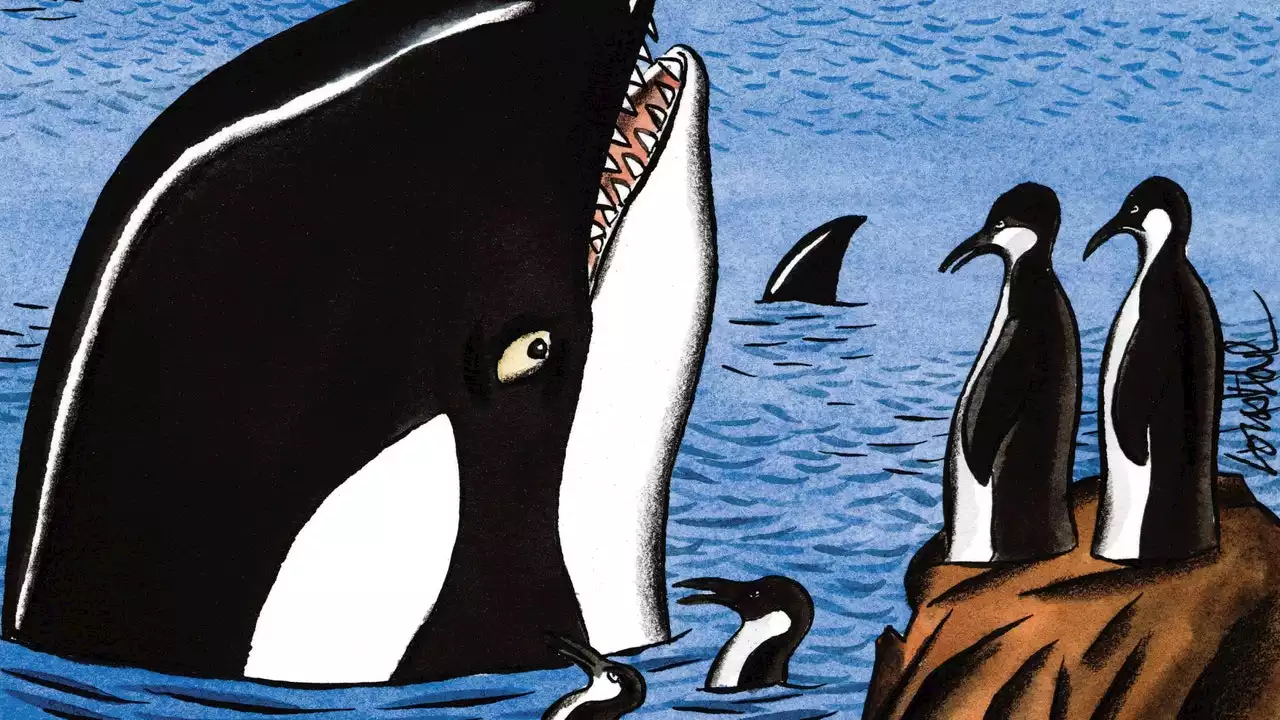

Despite Keiko’s progress, though, there was no irrefutable evidence that he would ever leave his bay pen permanently. During the winter, when the wild whales were gone, he was back in his pen full time, and he was the same tractable fellow as always, ready in a minute to put his big wet rubbery head in your lap. If he was getting an idea of what wildness was, he was still a bit of a baby, and certainly daintier than you might think a killer whale should be.