Along the way, physicists had to answer the question: “What happens if you pour hot tea into a black hole?”

Very little about black holes, among the strangest objects in the universe, is straightforward. Scientists have a more complete conception of these mind-bending objects than ever before, by studying the massive ripples black holes create in spacetime and learning about. But the brief history of humanity’s understanding of black holes was rocked with major twists and turns along the way.

Michell’s question was a good one. But a few years later, in the 1790s, the renowned French mathematician Pierre-Simon Laplace and other pioneering thinkers convinced the scientific community that light behaved like a wave and, therefore, was not affected by gravity, Mann says. This new conception of light made Michell’s theory look irrelevant.

Then, in 1939, physicists Rober Oppenheimer and Hartland Snyder tried to find out whether a star could create Schwarzschild’s impossible-sounding object. They reasoned that given a big enough sphere of dust, gravity would cause the mass to collapse and form a singularity, which they showed with their calculations. But once World War II broke out, progress in this field stalled until the late 1950s, when people started trying to test Einstein’s theories again.

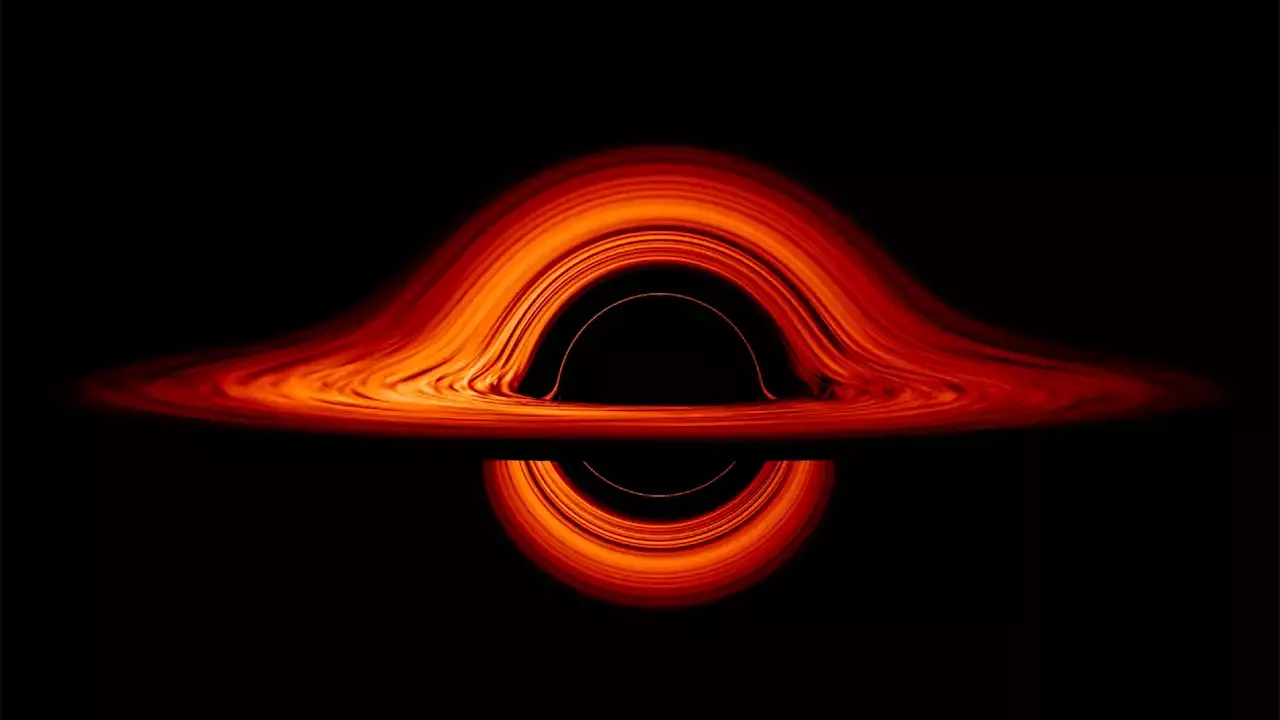

By the 1960s, these objects had a catchy name, “black hole.” The term explained two features: They were holes, in the sense that things could fall into them but never escape, and they would appear totally dark to any observers. “There is still no agreement on how to solve this problem,” Mann says, though some researchers believe they’re close to solving it.Hawking helped solve another mystery that had clung to black holes since the beginning. The black hole solution that Schwarzschild came up with in the early 20th century didn’t just prevent light from escaping. It also included a hole in spacetime at the core of the black hole–the singularity.