This article explores the ethical challenges faced by lawyers working for the War Relocation Authority (WRA) during the Japanese American internment during World War II. It examines their diverse responses, ranging from principled resignations to strategic accommodations, highlighting the complexities of navigating a system rooted in injustice.

Replica internment camp barracks stand at Manzanar National Historic Site on Dec. 9, 2015, near Independence, Calif. Manzanar War Relocation Center was one of 10 Japanese American internment camps.

With radical policy shifts looming in Donald Trump’s new administration, many federal employees are surely debating a difficult question: Resign? Or stick around for an agenda that troubles them? This moral calculus — whether to try to make a difference from within or leave in protest — has long challenged government workers, particularly in moments of ethical crisis. Eight decades ago, federal lawyers wrestled with this same dilemma as the government imprisoned more than 100,000 innocent Japanese Americans from the West Coast on account of their ancestry. Their responses — ranging from principled resignation to strategic accommodation — offer powerful lessons about the space between simply following orders and walking away entirely. For four years during World War II, the War Relocation Authority (WRA) managed the mass imprisonment of Japanese Americans. The agency’s own lawyers recognized the moral weight of their work — one attorney later acknowledged that it “unnecessarily caused immeasurable and irreparable suffering, hardship, and loss to the minds, bodies and properties of Japanese Americans. The agency itself conceded that the camps ‘were bad for the evacuated people and bad for the future health of American democracy.’” In 1943, one WRA lawyer chose to take a stand. Maurice Walk of Chicago resigned in protest, writing to his boss: “I am unable to collaborate in defense of a policy of which I so strongly disapprove.” He charged the agency with laying the legal groundwork for “future fascistic persecution of racial and political minorities” and wanted no part of it. Walk’s resignation, while inspiring, remained singular. No other WRA attorney followed his example of protest. It’s easy to condemn them for staying on the job — perhaps too easy. Walk was a consultant to the WRA who maintained a private law practice alongside his agency work. The others were full timers whose salaries were their livelihoods. Resigning, for all its moral allure, is a luxury for most working people.Those who stayed didn’t mindlessly carry out what they assumed to be their job. Instead, they found ways to use their discretionary power — though they often differed dramatically in how they wielded it. The protection of Japanese Americans’ property and economic rights became a crucial battleground. At the Gila River camp in southern Arizona, Jim Terry fought relentlessly against West Coast interests trying to fleece prisoners of property they’d been forced to leave behind. His advocacy extended to a fiery public display at a 1943 meeting of the Arizona Corporation Commission, where he took on bigoted state officials trying to drive the camp’s prisoner-organized stores and services out of business. The lawyers also sometimes worked to give prisoners more control over their daily lives at the camps. At Heart Mountain in northwest Wyoming, Jerry Housel defied his agency’s rules for punishing petty crimes, which called for a sort of drumhead court before the camp’s senior white administrator. Instead, he helped the prisoners create their own tribunal. When WRA headquarters in Washington objected, Housel stood his ground, and the tribunal survived, issuing judgments more reflective of the community’s values. Yet these same lawyers often responded differently — even contradictorily — when faced with decisions about camp conditions. When the Army announced plans to add another barbed wire fence tightly encircling the residential barracks, responses varied dramatically. At Heart Mountain, Housel — the same lawyer who had fought for prisoner self-governance — passively allowed the fence construction despite knowing it was unnecessary and offensive to the prisoners. Meanwhile, at the Poston camp in Arizona, Ted Haas actively resisted, leading the staff in a denunciation of the fence that halted its construction. These contradictions extended to individual lawyers’ treatment of the prisoners themselves. Terry, despite his fierce defense of economic rights, showed little patience for what he viewed as “troublemakers” resisting the WRA’s authority. His aggressive handling of loyalty hearings sometimes left prisoners in tears. Such inconsistencies revealed how even well-intentioned officials could perpetuate systemic injustice while trying to mitigate its worst effects.Trump’s claims about California water and L.A. fires are inaccurate and misleading, experts say The WRA lawyers were far from heroes. They gave their energies to a system they knew to be unjust. But in their best moments, they nourished an awareness of the suffering of the Japanese Americans around them. They kept their eyes open to the power they held to diminish it. I met Housel as an elderly man in 1997 and asked him about his time at Heart Mountai

Japanese American Internment WWII War Relocation Authority (WRA) Ethics In Government Legal History Moral Dilemmas

United States Latest News, United States Headlines

Similar News:You can also read news stories similar to this one that we have collected from other news sources.

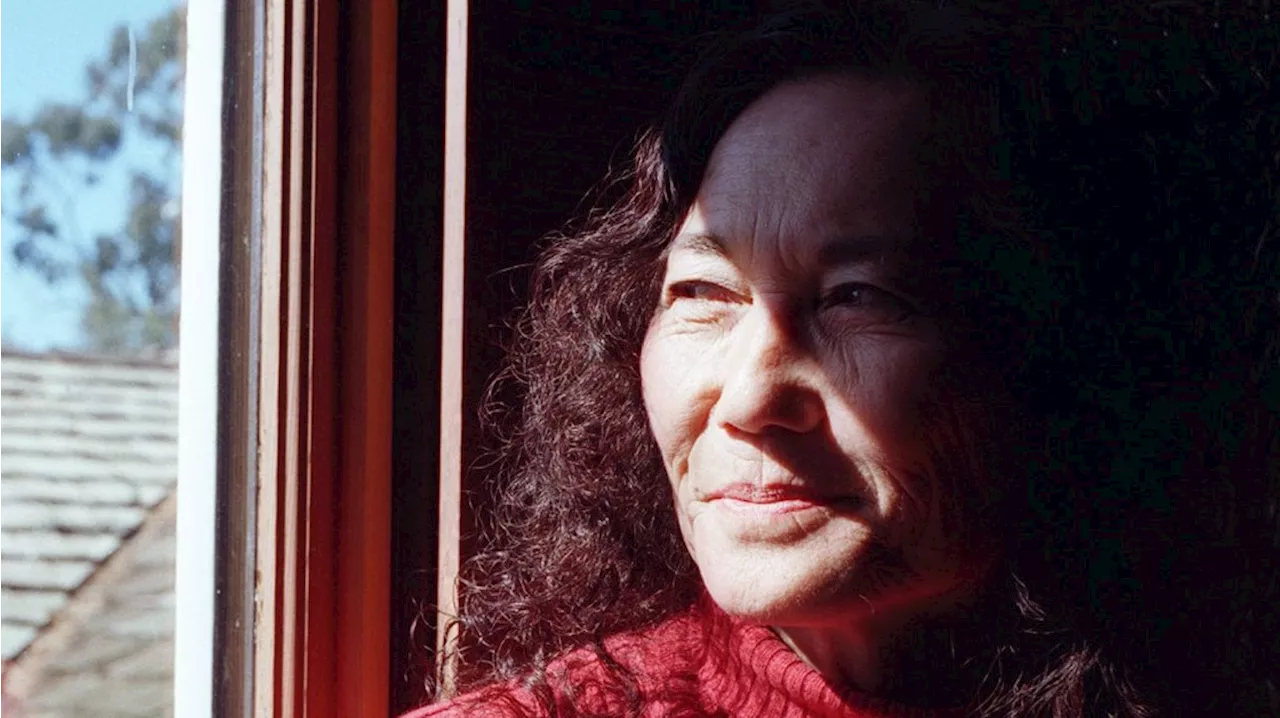

Jeanne Wakatsuki Houston, Santa Cruz author who chronicled Japanese internment experiences, dies at 90Jeanne Wakatsuki Houston, an acclaimed author who shared stories of growing up in a Japanese American internment camp during World War II in her 1973 memoir, “Farewell to Manzanar,” die…

Jeanne Wakatsuki Houston, Santa Cruz author who chronicled Japanese internment experiences, dies at 90Jeanne Wakatsuki Houston, an acclaimed author who shared stories of growing up in a Japanese American internment camp during World War II in her 1973 memoir, “Farewell to Manzanar,” die…

Read more »

Japanese-American Chef Sonoko Sakai Explores 'Wafu Cooking' in New CookbookSonoko Sakai's new cookbook, “Wafu Cooking: Everyday Recipes with Japanese Style,” explores the art of blending Japanese sensibilities and flavors with Western dishes. Sakai, a Japanese-American cooking instructor, defines wafu as “Japanese in style,” encompassing both culinary and presentation elements. She emphasizes the evolution of Japanese cuisine, showcasing how dishes like gyoza and tonkatsu, influenced by Chinese and French culinary traditions respectively, were adapted to embrace Japanese tastes and ingredients.

Japanese-American Chef Sonoko Sakai Explores 'Wafu Cooking' in New CookbookSonoko Sakai's new cookbook, “Wafu Cooking: Everyday Recipes with Japanese Style,” explores the art of blending Japanese sensibilities and flavors with Western dishes. Sakai, a Japanese-American cooking instructor, defines wafu as “Japanese in style,” encompassing both culinary and presentation elements. She emphasizes the evolution of Japanese cuisine, showcasing how dishes like gyoza and tonkatsu, influenced by Chinese and French culinary traditions respectively, were adapted to embrace Japanese tastes and ingredients.

Read more »

Jeanne Wakatsuki Houston, Inglewood-born author of ‘Farewell to Manzanar,’ dies at 90The acclaimed author shared stories of growing up in a Japanese American internment camp during World War II in her 1973 memoir.

Jeanne Wakatsuki Houston, Inglewood-born author of ‘Farewell to Manzanar,’ dies at 90The acclaimed author shared stories of growing up in a Japanese American internment camp during World War II in her 1973 memoir.

Read more »

Oshogatsu Festival welcomes 2025 at Japanese American National Museum in LAThis festival said hello to the new year on Sunday and looked forward to celebrating the Lunar New Year, Year of the Snake, later in January.

Oshogatsu Festival welcomes 2025 at Japanese American National Museum in LAThis festival said hello to the new year on Sunday and looked forward to celebrating the Lunar New Year, Year of the Snake, later in January.

Read more »

Oshogatsu Festival Celebrates New Year at Japanese American National MuseumThe Japanese American National Museum in Los Angeles hosted the Oshogatsu Festival on January 5, 2025, ushering in the new year with traditional festivities. Attendees enjoyed candy creations, Taiko drumming performances, craft activities celebrating the Year of the Snake, and readings from Japanese folktales.

Oshogatsu Festival Celebrates New Year at Japanese American National MuseumThe Japanese American National Museum in Los Angeles hosted the Oshogatsu Festival on January 5, 2025, ushering in the new year with traditional festivities. Attendees enjoyed candy creations, Taiko drumming performances, craft activities celebrating the Year of the Snake, and readings from Japanese folktales.

Read more »

WWII Japanese American Incarceration Mural Vandalized in Seattle's Chinatown-International DistrictArtwork dedicated to Japanese Americans incarcerated during WWII was vandalized in Seattle's Chinatown-International District on Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. Day. The mural in Nihonmachi Alley was smeared with black paint and covered with Bible verses, sparking outrage and discussion about the act's intent. Advocacy groups are calling for solidarity and for people to speak up against this act of vandalism.

WWII Japanese American Incarceration Mural Vandalized in Seattle's Chinatown-International DistrictArtwork dedicated to Japanese Americans incarcerated during WWII was vandalized in Seattle's Chinatown-International District on Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. Day. The mural in Nihonmachi Alley was smeared with black paint and covered with Bible verses, sparking outrage and discussion about the act's intent. Advocacy groups are calling for solidarity and for people to speak up against this act of vandalism.

Read more »