Mental health needs spiked during COVID-19. But how do you help people realize they need job help, and food, and counseling?

People who are in crisis might know they need food, or housing — tangible needs — but not realize they are also struggling mentally. This posed a challenge for agencies that try to help them. When people are in crisis, how do you carve out space for them to evaluate and address their well being?

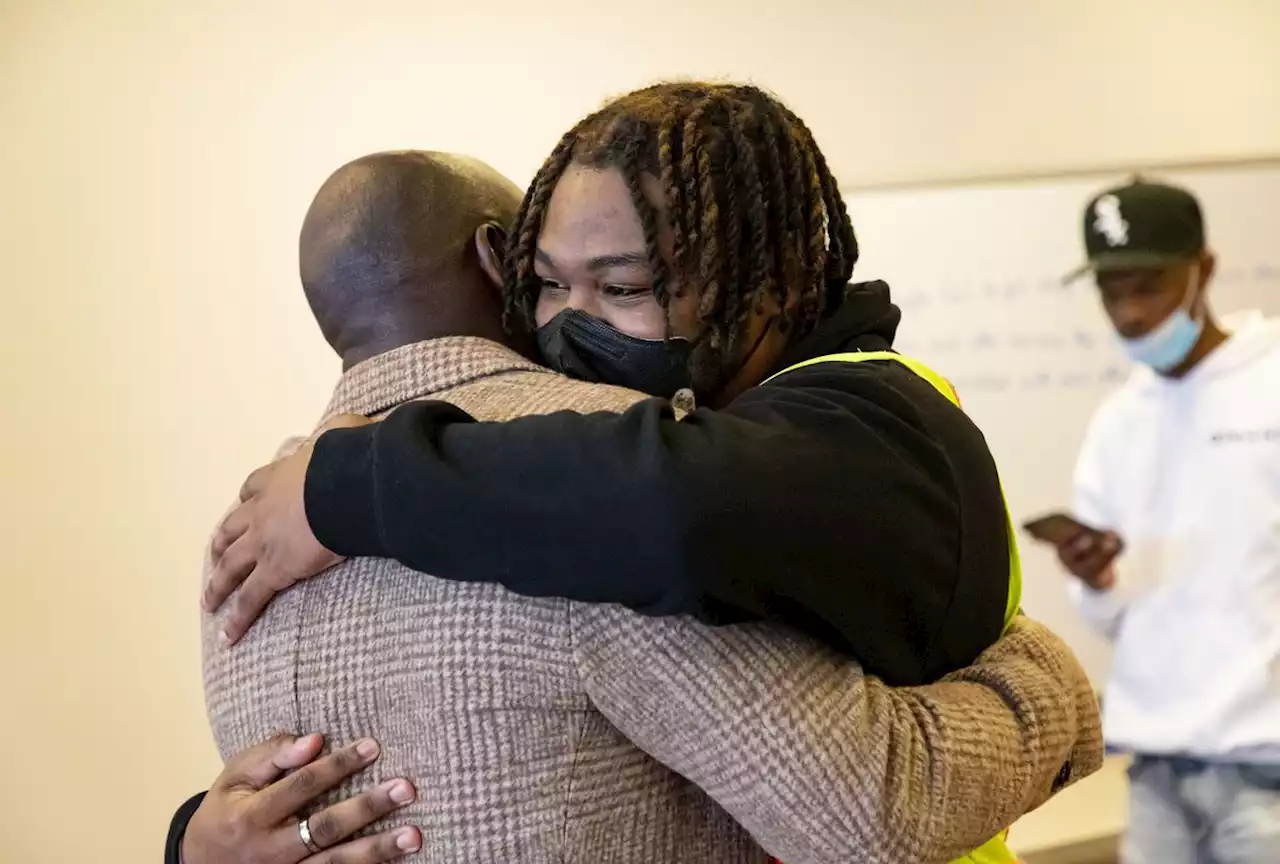

Heartland and other groups have extensive intake processes, often done by social workers, including questions such as asking about poor appetite, or thoughts they would be better off dead. They also employ people from the community with experiences that reflect those of the people they’ll be reaching out to.

Dominique Moore, 25, came to the YWCA after hearing about the job-training programs. It was May 2020, and she was feeling shaken by seeing jobs evaporate. Challenges are often interconnected. A lack of safe and affordable housing can be a barrier to substance abuse recovery, for example, or someone seeking work experiences anxiety. “How do you manage your stress and anxiety while you’re looking for work, while you’re feeling like, I have to get this job?” Hull said.

. It cited accounts from Illinois counseling centers having trouble finding applicants or filling vacancies.Although the Kaiser Family Foundation data remains similar, showing 24% of mental health needs can be met, advocates and officials say the pandemic made it more difficult for people to access therapy because of shortages and by adding pressure to safety net services.

an Illinois Behavioral Health Workforce Center, which will be housed at the Southern Illinois University School of Medicine and the University of Illinois at Chicago to research shortages and boosting the workforce.In the meantime, groups are getting creative about how to help people.